His creative contribution, namely “Operation Eternity”, has made him immortal. These are some insights of his life and his 57,5 years with IWC. Click on “read more” to get the 4 pages story with lots of pictures…

Kurt Klaus, who turned eighty on 26 October, recently stated the following: “I’m a happy man and I’m content with my life.” And the fact that he is now regarded as something of an old hand at IWC founded in 1868 is something he is pleased to acknowledge. But the story of his time in Schaffhausen, now exactly 57 and a half years, is not over yet.

His desk is still at the company’s head office. Just a few days ago, he returned from yet another of his trips abroad as a watchmaking “missionary” that have taken him, among other places, to China and Korea. When Kurt Klaus travels, he not only uses his fascinating knowledge of classic watchmaking to promote this intriguing profession, he has also been a part of the world of watchmaking for longer than most and has played a significant role in some of its most important developments. He is therefore qualified to convey a genuine passion for this traditional craft to lovers of fine timepieces in new and distant markets. People listen to what he has to say.

Kurt Klaus, who grew up in St. Gallen, wanted above all to be a good watchmaker, a vocation that has always enjoyed considerable respect in Switzerland and attracts individuals whose personal qualities include composure, introversion, infinite patience and a willingness to learn. Klaus possessed them all and from 1951 spent 4 years at the watchmaking school in Solothurn. After successfully concluding his training, he completed his military service in several stages and worked at Eterna in Grenchen before setting his sights on finding a permanent job in 1956.

“But not in Grenchen!” insisted his then girlfriend and future wife. And so Kurt Klaus approached IWC in Schaffhausen: “Could you use a young watchmaker?” He immediately received a letter inviting him to an interview. None other than IWC’s Technical Director Albert Pellaton, whose name was already well known in watchmaking circles, signed it. Some years previously, he had invented the 85-calibre automatic movement, the first from IWC to feature the Pellaton winding system named after him and made it ready for the market.

Klaus hopefully laid his impressive school reports on Pellaton’s desk, only to be told something that was to influence his attitude towards working at IWC forever: “But you should know that being a watchmaker at IWC means going a step further than this.” It was then, for the first time, that he encountered the relentless quest for quality that has been part of the company’s DNA since F. A. Jones founded it. And he has never forgotten it.

“Yes, I went through Pellaton’s training,” Kurt Klaus proudly told me. This meant starting right at the bottom, assembling wheel trains and escapements. Then, as a member of the service department, the range of tasks assigned to him became gradually wider, the work more demanding. Pellaton recognized his abilities as a design engineer and problem solver and gave him the chance to prove himself assembling prototypes. Klaus can tell a wealth of anecdotes from this period, all of which relate to the quest for perfection. Pellaton’s praise was always stinted, at times so faint as to be almost imperceptible: “Yes, it’s good, but it could be just a bit better.” If he was in parts production, looking over the shoulder of someone rolling out bearing pivots within the permitted tolerance of 0.003 millimetres, he might have been hard to say: “You don’t have to make full use of the tolerance, you know.”

In the mid-1970s, after a long period of prosperity, the industry was rocked by the quartz crisis. It led to short-time working and a number of what were known as survival tactics. Klaus, for example, found himself mounting calendars onto pocket watch movements. These watches were magnificent specimens that initially sold very well. But, ultimately, the pocket watch had had its day.

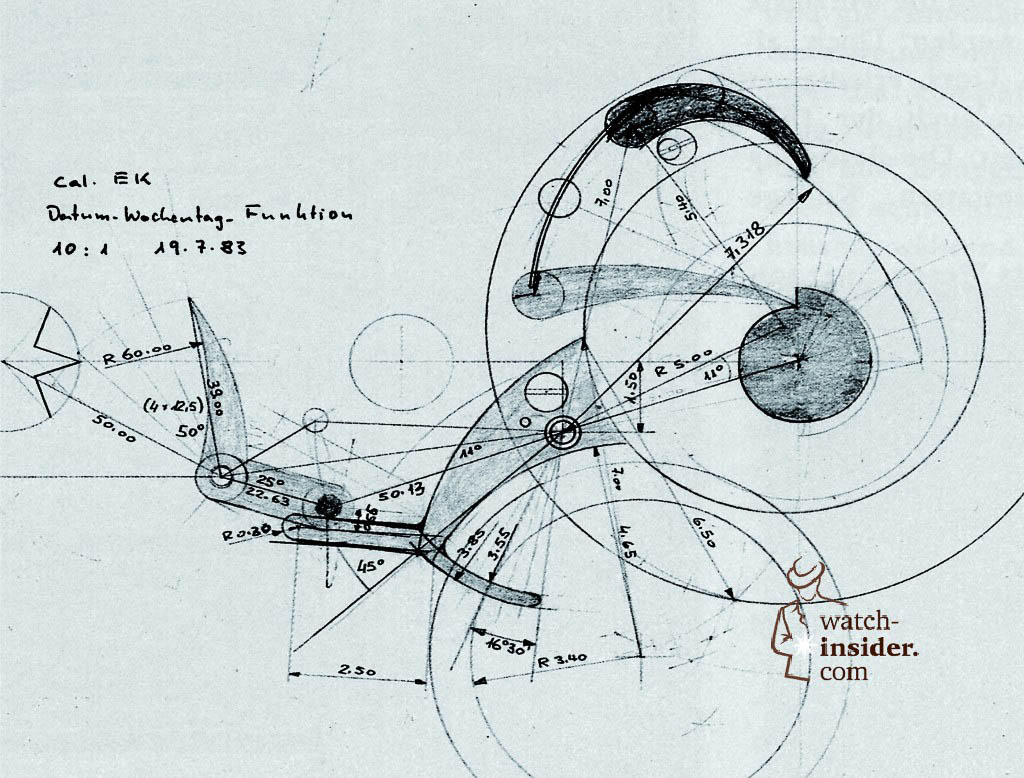

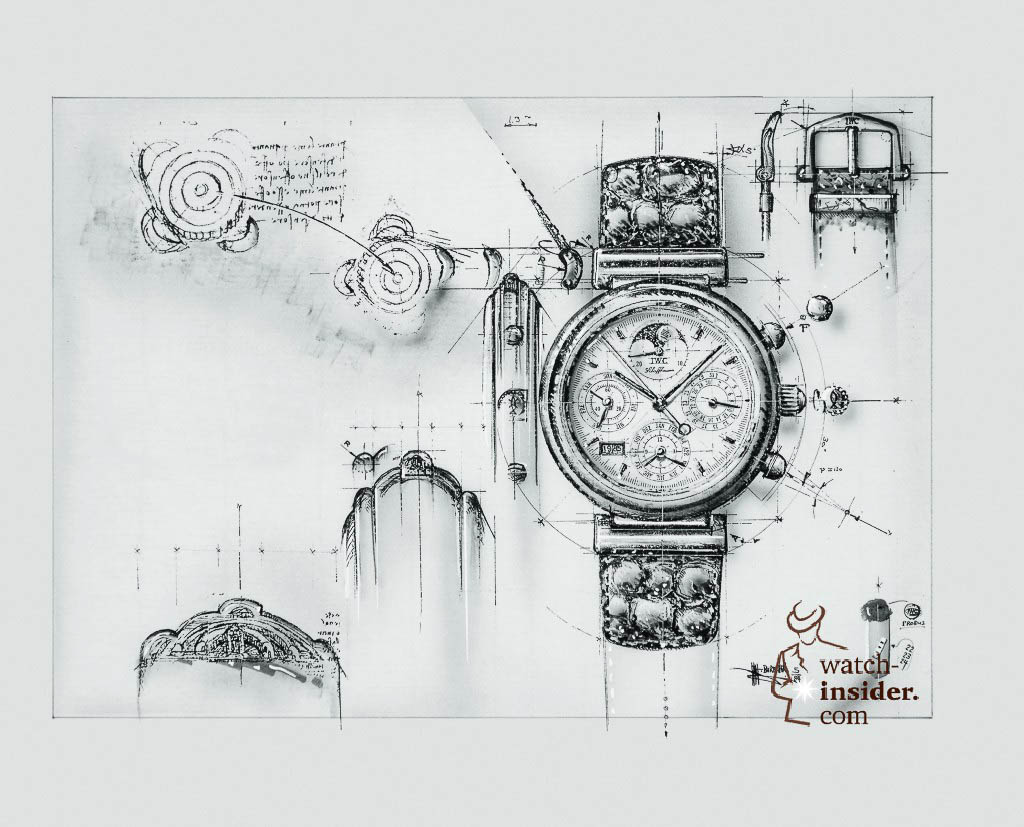

After its acquisition by German instrument makers VDO Adolf Schindling AG, under the leadership of the new CEO Günter Blümlein, IWC joined forces with Porsche Design to create some impressively large, sporty wristwatches using titanium. At the same time, Blümlein’s deputy and sales director Hannes Pantli urged Klaus to put his expertise to use in the design of a wristwatch with a perpetual calendar. It was all very well making sports watches, but traditional watchmaking could not be allowed to suffer. Klaus needed no second invitation. His very first draft, traditionally drawn by hand and with the numbers worked out on a calculator, incorporated all the basic ideas that later went into the final design. Blümlein recognized its potential immediately, gave the project his approval and suggested that it might be a good idea to combine the promising innovation with a chronograph movement. The two had never before been united in a single watch.

Klaus perfected the details for 4 years with the help only of a draughtsman, without CAD – or even a computer at all. He would work on his vision until late in the evening and at weekends, and in the process listened to the entire oeuvre of his favourite composer, Vivaldi, time and time again. He would go for long walks in the woods close to Schaffhausen, searching his mind for the answer to the main problem: how to transmit the single date switch in the basic movement at midnight synchronously to all the other calendar displays and ensure that they all advance as dictated by the leap year cycle.

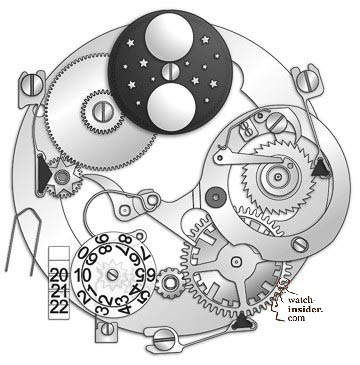

He found the solution. Put in the simplest possible terms, it consists of a pivoting multifunctional lever with a pawl, the tip of which rests on the month cam, where it reads the length of the months. At the end of the month, the mechanism advances the date wheel by 1 day (months with 31 days), 2 days (months with 30 days), 3 days (February in a leap year) or 4 days (February in a normal year). A cam and an additional pawl ensure that everything advances correctly in the short months. Another gear chain leads off to the year display, while an advance finger moves the precisely calculated wheels of the moon phase display.

Klaus milled and turned the wheels and parts for this mechanism himself in a small workshop next to his office. He was still assembling the first movements for the Da Vinci and fitting them into their elegant gold cases the night before the opening of the Basel watch show in 1985. In the end, “Operation Eternity” became a close-run race against time; something in which Klaus was not short of experience. Until just a few years ago, whenever he had the opportunity he would enter his whippets in the greyhound races. He still has the trophies in his apartment. But even after the Da Vinci’s enormous success, he was still made to wait for his “trophy” as an inventor, and there was no way he could rest on his laurels. In 1987, Hannes Pantli took him along on a trip to Asia for the first time. In Singapore, Hong Kong and Tokyo, Klaus taught watchmakers how to correct his perpetual calendar. All the displays could be advanced synchronously using only the crown, but could not be turned back, as discovered by some owners who were simply unable to resist the temptation to see for themselves whether the movement would really advance to the next year or decade. This new task of sharing his knowledge with his colleagues was one he warmed to from the start. On working with the great innovator, Hannes Pantli has this to say: “It is impossible to overestimate the contribution Kurt Klaus has made towards the survival of the mechanical watch and to IWC. He perfectly combines his visionary gift and firm belief in the future of watchmaking with a natural human warmth and affability. It has always been a great pleasure to work with him.”

>>> Continue to read the story on page 2 >>>

It is truly remarkable that the De Venci was drawn by hand. This alone I believe places Mr Klaus in the category of “all time greats” of the Swiss watch industry. Can you imagine creating this via hand drawing and a calculator, wow, that’ s incredible. On a human perspective and never have meet the man, he looks like a humble warm hearted professor whom I sure is as classy as the watches he has designed… Salute Mr Klaus

Thanks for this wonderful article Alexander

jeff

It’s incredibly creative people like Mr Klaus, storied watch companies like IWC, and well written articles like this by Alexander, is exactly why I have such a passion for watches.

The others have said it all and I ditto all their comments.

Great article!

Alex, it’s stories like this that keeps me returning to your site.

I hold it at the highest praise for all horlogerie matters, but you consistently provide so much more.

Bravo!

Umpteen Happy Returns Of The Day Mr. Klaus!

You are 80 years young, so keep on creating great timepieces!

Dear Mr. Klaus,

Salute to you on your 80th birthday.

Long live for newer and newer extraordinarily

designed mechanical watches.

Nilesh D Mistry

This is exactly why mechanical watches have “souls.”

People like Mr. Klaus put their talent, skills, time, effort, genius and really their whole lives into them.

That is why I love mechanical watches.

Happy Birthday Mr.Klaus.